Part 1: Liberty or Coercion?

A momentous stand-off is about to take place. The atmosphere is spellbound. Hundreds of dignitaries are present in the assembly hall. Crowds are gathered outside in the streets. The two men stand eye to eye for the first time. Both are young, one 21 years, the other 38 years.

One, the most powerful ruler of the nation, the other, a believer of deep conviction. One, whose words decide the fate of a person's earthly life, the other, whose words impact a person's eternal life. One, leaning on worldly authority, the other, leaning on heavenly authority. It is a historic showdown between authority and conscience.

Welcome to the Diet of Worms in Germany on April 18, 1521. Martin Luther stands before Emperor Charles V and is asked if he recants his publications. The final words of his response spark a revolution on conscience:

"Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures, or by clear reason, I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted, and my conscience remains captive to the Word of God. ... I cannot and will not recant, because it is neither safe nor advisable to go against one's conscience. God help me. Amen." [1]

The Reformation began as a call for liberty of the individual conscience. Liberty of conscience is the foundation upon which all other liberties rest. There can never be "religious liberty" unless there is already "liberty of conscience". A core issue at stake globally across all levels of society in our current world context is "liberty of conscience". This term is deeper and broader than "religious liberty", as typically used and oft-time misunderstood in Adventist discussions. The preferred term to explore is "liberty of conscience".

In a three-part series we will reflect on "conscience" and its relevance for us in the current world context. This Part 1 explores the history of the cause of conscience and some aspects of "liberty of conscience" and "coercion of conscience" (be sure to get the downloadable resource file towards the end of the article). We begin by embarking on a journey through history and starting with Martin Luther.

1. Martin Luther

For Luther, the voice of conscience was seen as the "point of contact" between God's revelation and the human being.[2] Man is guided by conscience as he communicates with God. Conscience was for him at the heart of faith, the "bearer of man's relationship with God" and the "religious root of man".[3] Luther regarded all meaningful religious experience as an experience of conscience.[4] He also realized that conscience needs an external source of guidance, thus appealing to conscience as directed by Scripture.[5]

Luther introduced a shift in the understanding of conscience, from the institutionally bound conscience of Catholicism to a "Reformation" conscience, bound by its communication with God and by Scripture.[6] His closing words at Worms asserted the supremacy of such a conscience over human and ecclesiastical authorities.[7] This was a crucial moment in the development of future, fundamental rights.[8] The idea of religion being based on personal conscience was nothing short of a revolution.

In the early 1520's, Luther wrote in favor of toleration, being opposed to persecuting dissenting believers, and advocating liberty of conscience.[9] Tragically, in the years following the Diet of Worms, he shifted from liberty of conscience as he supported a union of his embryonic church and the state.[10] Influenced by events of the German Peasants War and the Anabaptist movement, he gradually reached the point of urging the state to root out dissenting Christians by force.[11] Luther's shift became evident at the Diet of Speyer in 1529.

This Diet is known for the "Protest of the Princes", where the Lutheran delegates rejected the "Resolution" of the Diet which reinstated the Edict of Worms (issued 1521 at Diet of Worms, temporarily suspended 1526). The Edict legislated that Martin Luther, all of his writings and anyone spreading his cause would be nationally outlawed, subjected to confiscatory penalties and a death sentence. The "Protest document" claimed the rights of conscience by stating "we should have nothing to answer before God, should anybody, ... separate from the doctrine ... of the eternal word of God ... and against our own conscience".[12]

This Diet is less known for the fact that the same Lutheran delegates supported the "Anabaptist Mandate", in which "each and every rebaptizer and rebaptized person [Anabaptists] ... shall be brought ... to death".[13] The Lutheran delegates claimed the rights of conscience for themselves, while denying them to other Christians.

Despite Luther not granting full liberty of conscience to others, the seeds he sowed would yield fruit in future generations. Next in line to promote the cause of conscience were the Anabaptists.

2. Anabaptists

In the wake of the Reformation during the 1520's, Anabaptists arose throughout Europe.[14] They were known to be peaceful, constructive and tolerant, desiring to follow Bible teachings without adding human traditions. Some beliefs were that the Bible is the source of authority for a Christian, necessity of a new birth, adult believer's baptism, regenerate church membership, liberty of conscience, and separation of church and state.[15]

Their doctrine of adult baptism underscored the principle of liberty of conscience because each person makes a decision based on conscience.[16] Their doctrine of separating church and state underscored the same principle.[17] Anabaptists were the first to develop a systematic view on liberty of conscience.[18] While their refusal to recognize infant baptism brought great opposition, it was their rejection of church-state establishments that resulted in even more persecution.[19] They broke completely with the state-church system, which the main Reformers retained. The Anabaptist concept of liberty of conscience was far ahead of its time and in conflict with both Catholics and Protestants.[20]

Balthasar Hubmaier [21], a German Anabaptist leader, stated in the 1520's regarding conscience, that "judge in your mind and according to your conscience based on the true simple Word of God”.[22] Menno Simons[23], a Dutch Anabaptist leader and father of the Mennonite groups, stated that spiritual matters “are not subject to human authority, but are the exclusive concern of God Almighty".[24] In his tract "A Brief Complaint or Apology" (1552) he asked: "Say, beloved, where do the Holy Scriptures teach that we shall rule the consciences and faith of others ... In what instance has Christ and the apostles ever done, recommended or commanded this?".[25]

The cause of conscience was not lost despite the widespread eradication of Anabaptists through persecution by Catholics and Protestants. Next in line to uphold the was the Baptist lineage.

3. Baptists

In 1608, John Smyth[26] and Thomas Helwys[27], ministers in England among Puritan separatists, left their homeland to find religious refuge in the Netherlands. There they discovered the biblical teaching of baptism and developed principles on liberty of conscience.

John Smyth stated in "Propositions and Conclusions" (1611),

"the magistrate [state] is not by virtue of his office to meddle with religion, or matters of conscience, to force and compel men to this or that form of religion or doctrine; but to leave Christian religion free, to every man's conscience."[28]

This was the first confession of faith of modern times officially demanding liberty of conscience and the separation of church and state. Thomas Helwys declared in "A Short Declaration of the Mystery of Iniquity" (1612) that "the King has no more power over their consciences than ours, and that is none at all".[29]

John Smyth remained in the Netherlands, eventually joining the Mennonites (Anabaptists), while Thomas Helwys returned to England, officially founding the Baptist Church in 1612.

4. The New World

In the 1630's the cause of conscience reached a new level through Roger Williams.[30] Initially a Puritan separatist minister in England, he emigrated to the New World due to religious intolerance in England, arriving in Boston and the Puritan-influenced "Massachusetts Bay" colony in 1631.

Before in England he had realized the effects of intolerance, and that its remedy was liberty of conscience and separation of church and state. Williams promoted these ideas at "Massachusetts Bay". Instead of openness, the colony put Williams on trial, banishing him in 1635. He eventually founded the colony "Providence" (Rhode Island) in 1636.[31] From here into the 1640's, Williams developed the most comprehensive view on the nature and protection of conscience up to his time. His principles are extensively presented by Edward J. Eberle and summarized below.[32]

4.1 Williams on the nature conscience

First, its sacred nature. Conscience is God's gift. It is the medium by which man communicates with God. Conscience receives truth that illuminates the path to God and guides one's way to salvation. Conscience is the basis by which man becomes a believer and constitutes the essence of religion and the fulcrum upon which religion rests. Matters of conscience extend beyond questions of belief. They also involve actions motivated by conscience. A divinely guided conscience is man's duty to God. To be true to God is to be true to conscience. Fidelity to conscience is a matter of freedom and obligation to do God's will. Conscience is thus inviolable and sacred.

Second, its universal nature. Conscience is an indispensable aspect of being human. It is found in all of mankind. Every person possesses a conscience.

Third, the nature of liberty of conscience. Due to the sacred and universal nature of conscience, liberty of conscience is the wellspring of human thought and belief. Liberty of conscience is the foundation of religion as a right, the foundation of religious liberty, the foundation of human rights, and the foundation of all other liberties. Man can only be free when conscience is secure from coercion.

Fourth, the nature of coercion of conscience. Due to the sacred nature of conscience, coercion of conscience is an infringement of God's domain. To violate conscience is to violate God's work and man's dignity. Forcing conscience undercuts man's right to communicate with God. It is a transgression of authority. No person or authority is justified to intrude into the sacred realm of conscience. To coerce conscience to something not voluntarily subscribed to, is "soul rape". There is no place for coercion of conscience in civil society.

4.2 Williams on the protection of conscience

First, the principle of equal rights. Due to the universal nature of conscience, all people are entitled to the same rights to exercise conscience. The state must give all persons equal terms of rights to conscience. All must be guaranteed the liberty to believe, and to act on that belief, according to conscience.

Second, the principle of toleration. Since conscience is of an individual and sacred nature, toleration is necessary. The principle of toleration follows the concept of conscience. Because conscience is inviolable, the proper course for authorities, when faced with acts of conscience, is to allow the person his or her choice. Conscience is the absolute barrier through which authorities may never intrude. Authorities reach their limit at the point where a person's conscience is reached. The proper role of authorities is to defend and uphold liberty of conscience principles.

Third, the principle of separation. Due to the presence of both religious and secular authorities in society, religion must be protected and insulated from state overreach. When separation is not respected, the price paid is coercion or conformity of conscience. Separation means maintaining purity of religion. The essence of religion is conscience. The essence of the state is law and order.

5. Era of Enlightenment until modern times

The cause of conscience has distinctly Protestant roots, whose main principles were established already half a century before the Enlightenment era, especially through Roger Williams. During the Enlightenment, philosophers took up the cause of conscience, though more from a rationalistic rather than a biblical perspective. Regarding conscience, one such philosopher, John Locke[33], stated in his "A Letter Concerning Toleration" (1689) that societal-religious discord:

"would soon cease if ... all churches were obliged to lay down toleration as the foundation of their own liberty, and teach that liberty of conscience is every man's natural right, equally belonging to dissenters as to themselves; and that nobody ought to be compelled in matters of religion either by law or force. The establishment of this one thing would take away all ground of complaints and tumults upon account of conscience."[34]

Since the Enlightenment, the cause of conscience was increasingly seen as a natural and human right. From the 1700's, these ideas gradually flowed into national constitutions throughout the world, eventually becoming a constituent part of modern Western societies. By the 20th century, the United Nations issued its "Universal Declaration on Human Rights" in 1948, which includes a strong protection for conscience-based beliefs and actions, stating:

"Article 18: Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance."[35]

6. Ellen White and "Liberty of conscience"

Ellen White shows strong support for the cause of conscience, viewing "liberty of conscience" as an end-time evangelistic theme, as a Protestant legacy, as a principle to be defended by the church, as a right to be protected by earthly authorities, and how God and Satan are total opposites in the liberties of conscience (see full quotes in footnote or downloadable PDF-file).[36]

7. Relevance for Adventists today

There is both a Protestant legacy of conscience and a current world context to keep in mind. In the end, we have just two options, either "liberty of conscience" or "coercion of conscience". Based on the insights above in this article, we can summarize the two as follows:

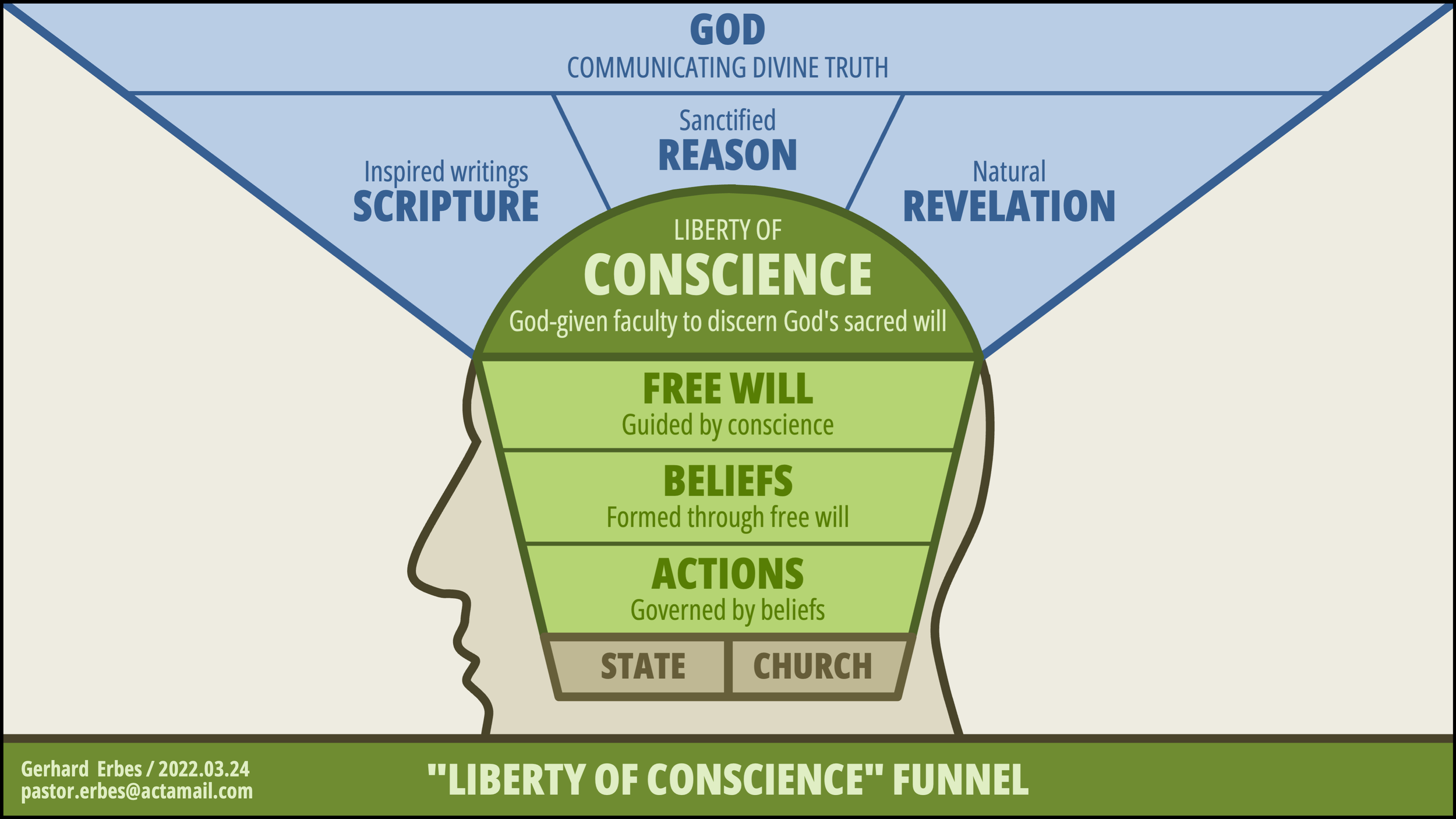

"Liberty of conscience" is only possible when man can freely communicate with God, and the Holy Spirit can interact with conscience through channels like inspired writings, sanctified reason, and natural revelation. Where the sacred ground of divine-human interaction within conscience is protected, there is liberty of conscience. This liberty is at the very center of man. Even deeper than "free will". While free will is the ability to choose, it still must be guided in its decisions. Conscience is that guide, but it can operate properly only when liberty of conscience is granted. As free will is guided by conscience, it forms "beliefs". These beliefs govern the "actions" taken. Liberty of conscience is like a funnel, from top to bottom, from divine truth down to human action, with conscience at the epicenter. Authorities such as church and state are subordinate to a divinely guided conscience and should defend liberty of conscience. See Illustration #1: "Liberty of Conscience Funnel".

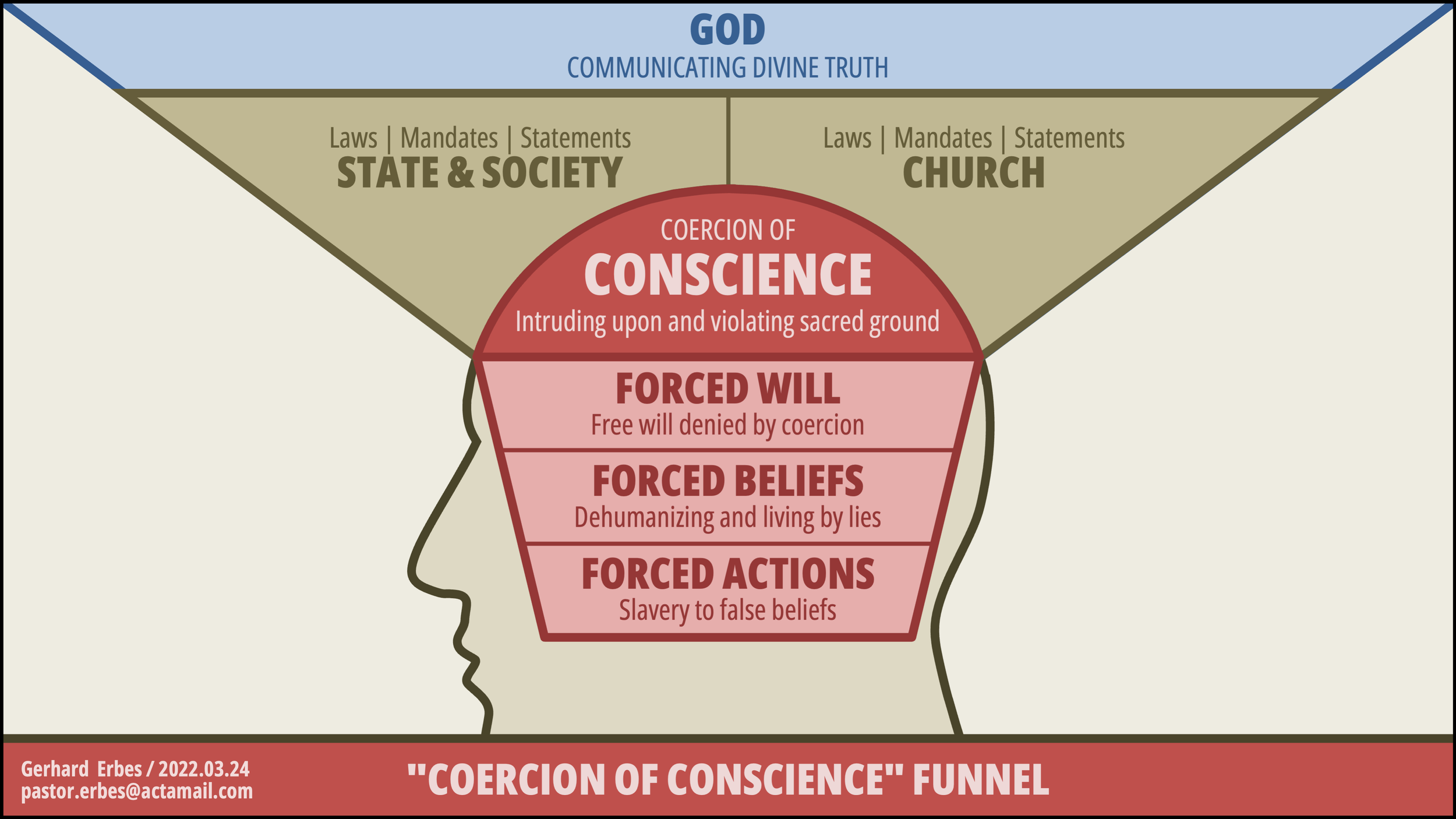

"Coercion of conscience" is the situation, where man's communication with God is interfered by human instrumentalities, placing themselves between man and God. Conscience, being the sacred ground of God's interaction within man, is being violated and intruded into. Free will is being denied by coercion, resulting in a "forced will". This results in the formation of "forced beliefs". Such beliefs destroy God's work in man and human dignity because they dehumanize and makes man live by lies. Forced beliefs lead to "forced actions". Forced actions done against one's conscience subject man to the slavery of false beliefs. Coercion of conscience is a similar funnel, but where human powers interfere, "raping the soul" and subjecting it to "soul slavery". See Illustration #2: "Coercion of Conscience Funnel".

As a church, we want to clearly stand up for the Protestant legacy of "liberty of conscience" handed down and entrusted to our generation. Staying silent to anything resembling "coercion of conscience" should never be an option we want to consider.

In Part 2 we continue exploring some deeper aspects of conscience, its scope, and its liberties, also asking questions concerning whether certain mandates in our current world context are "mole-hills" to be ignored or real "mountains" to be challenged, and if there is a calling to our church to not only defend liberty of conscience, but even to preach it evangelistically. Stay tuned!

ILLUSTRATION #1: Liberty of Conscience Funnel

ILLUSTRATION #2: Coercion of Conscience Funnel

****

Gerhard Erbes (PhD), originally a research scientist in physics who transitioned into ministry and previously lived in Austria, Germany and Sweden, presently serves as pastor of the SDA churches in Fairplain, Coloma and Hartford in Michigan. His marriage with Tilly is a personal blessing from a loving Heavenly Father.

[1] "Verteidigungsrede auf dem Reichstag zu Worms" (Full transcript of Luther's speech at Worms, in German, here translated literally). https://www.worms.de/en/web/luther/Worms_1521/Reichstag/Luthers_Rede.php.

[2] Forell, G. (1975). Luther and Conscience. The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg Bulletin, Vol. 55, Nr. 1, pp. 3-11. https://www.elca.org/JLE/Articles/991

[3] Berman, H. J. and J. Witte Jr. (1989). The transformation of Western Legal Philosopy in Lutheran Germany, Southern California Law Review, Vol. 62, Nr. 6, pp. 1575-1660. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1851133

[4] Baylor, M. G. (1977). Action and Person: Conscience in Late Scholasticism and the Young Luther, in H. Oberman ed., Studies in Medieval and Reformation Thought, Vol. 20. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1977, p.7.

[5] Blackburn, B. S. (2020). De Libero Conscientia: Martin Luther’s Rediscovery of Liberty of Conscience and its Synthesis of the Ancients and the Influence of the Moderns. Liberty University Journal of Statesmanship & Public Policy, Vol. 1, Iss. 1 , Article 11, pp. 1-17. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jspp/vol1/iss1/11

[6] Strohm, P. (2011). Conscience: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 24.

[7] Davis, T. A. (1977). Conscience: Your Inner Voice. Wildersville, TN: Orion Publishing, p. 21.

[8] Eberle, E. J. (2005). Roger Williams on Liberty of Conscience. Roger Williams University Law Review, Vol. 10, Iss. 2, Article 2, pp. 289-323. http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol10/iss2/2

[9] Wallace, E. G. (2009). Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition. Penn State Law Review, Vol. 114, No. 2, pp. 485-570. PDF-file: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1687244

[10] Horsch, J. (1907). Martin Luther's Attitude toward the Principle of Liberty of Conscience. The American Journal of Theology, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 307-315. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3153716?seq=1

[11] Wallace, E. G. (2009). Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition. Penn State Law Review, Vol. 114, No. 2, pp. 485-570. PDF-file: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1687244

[12] Charles (2011, January 17). The Protest at Speyer 1529. Northern Catholic Archives. https://northerncatholicarchives.wordpress.com/2011/01/17/the-protest-at-speyer/. (Comment: Contains the original full protest document, translated to English.)

[13] Hege, C. (1959). Diet of Speyer (1529). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Diet_of_Speyer_(1529).

"Wiedertäufermandat“ ["Anabaptist Mandate"]. In: Wikipedia. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiedertäufermandat. Contains parts of the original German "Anabaptist Mandate".

[14] Kutilek, D. (2017). Anabaptists: the Real Heroes of the Reformation. Baptist Bible Tribune, October 31, 2017. https://www.tribune.org/anabaptists-the-real-heroes-of-the-reformation-doug-kutilek/

[15] Wallace, E. G. (2009). Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition. Penn State Law Review, Vol. 114, No. 2, pp. 485-570. PDF-file: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1687244

[16] Witte, J. Jr. (2020). The Right of Freedom of Religion: An Historical Perspective from the West. In S. Ferrari et al., eds., Routledge Handbook on Freedom of Religion and Belief, pp. 9-24. London: Routledge. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3959070

[17] Witte, J. Jr. (2020). The Right of Freedom of Religion: An Historical Perspective from the West. In S. Ferrari et al., eds., Routledge Handbook on Freedom of Religion and Belief, pp. 9-24. London: Routledge. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3959070

[18] Wallace, E. G. (2009). Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition. Penn State Law Review, Vol. 114, No. 2, pp. 485-570. PDF-file: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1687244

[19] Wallace, E. G. (2009). Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition. Penn State Law Review, Vol. 114, No. 2, pp. 485-570. PDF-file: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1687244

[20] Bender, H. S., N. van der Zijpp and T. J. Koontz. (1989). Church-State Relations. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Church-State_Relations&oldid=173131

[21] Britannica, Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022). Balthasar Hubmaier. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Balthasar-Hubmaier

[22] Pipkin, H. W. and J. H. Yoder (1989): Balthasar Hubmaier: Theologian of Anabaptism. Scottdale, PA.: Herald Press, p. 99.

[23] Dyck, C. J. (2022). Menno Simons. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Menno-Simons.

[24] Wallace, E. G. (2009). Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition. Penn State Law Review, Vol. 114, No. 2, pp. 485-570. PDF-file: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1687244

[25] Simons, M. (1552). A Brief Complaint or Apology. In J. F. Funk, The Complete Works of Menno Simons. Elkhart, IN: J. F. Funk & Brothers, p. 118. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Complete_Works_of_Menno_Simons/A_Brief_Complaint_or_Apology_of_the_Despised_Christians_and_Exiled_Strangers.

[26] Britannica, Editors of Encyclopedia (2021). John Smyth. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Smyth.

[27] Britannica, Editors of Encyclopedia (2013). Thomas Helwys. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Helwys.

[28] Shurden, W. B. (1996). How We Got That Way: Baptists on Religious Liberty and the Separation of Church and State. Presented at Baptist Joint Committee’s 1996 Religious Liberty Conference. https://bjconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/How-We-Got-That-Way.pdf

For Smyth's original full text of "Propositions and Conclusions", see: http://www.reformedreader.org/ccc/acof1612.htm

[29] Shurden, W. B. (1996). How We Got That Way: Baptists on Religious Liberty and the Separation of Church and State. Presented at Baptist Joint Committee’s 1996 Religious Liberty Conference. https://bjconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/How-We-Got-That-Way.pdf

[30] Britannica, Editors of Encyclopedia (2021). Roger Williams. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roger-Williams-American-religious-leader

[31] Neumann, C. E. (2009). Roger Williams. The First Amendment Encyclopedia. https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1231/roger-williams

[32] Eberle, E. J. (1999): Roger Williams' Gift: Religious Freedom in America". Roger Williams University Law Review, Vol. 4, Issue 2, pp. 425-486. https://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1102&context=rwu_LR

Eberle, E. J. (2005). Roger Williams on Liberty of Conscience. Roger Williams University Law Review, Vol. 10, Iss. 2, Article 2, pp. 289-323. http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol10/iss2/2

[33] Rogers, G. A. J. (2021) John Locke. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Locke

[34] Locke, J. (1689). A Letter Concerning Toleration. Latin and English texts revised and edited by Mario Montuori. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1963. https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendI_assemblys7.html

[35] United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

[36] Selected Ellen G. White statements on "conscience" and "liberty of conscience":