Chappaquiddick - Never Ride With a Kennedy

On the evening of July 18, 1969, as Aldrin, Armstrong, and Collins were halfway to the moon, Senator Edward Kennedy, youngest brother of the president who set the moonshot in motion, was attending a beach party on Chappaquiddick Island

Kennedy’s party, at a rented beach house called the Lawrence cottage, was attended by six single women in their 20s and six older, married men.

Ariel view of Chappaquiddick Island

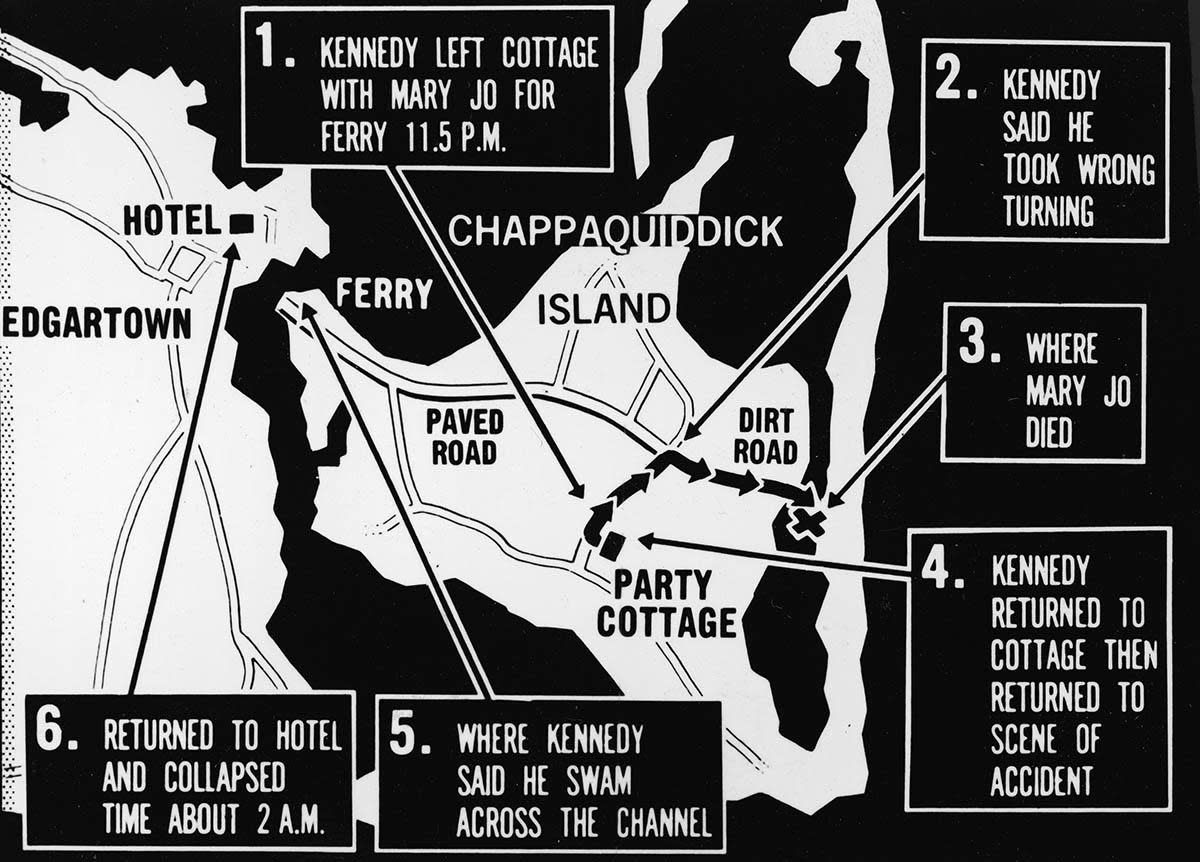

At some point late in the evening, Kennedy left the party with 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne. Kennedy later testified that Kopechne told him she wanted to go back to her hotel, but she told no one else, and she left her purse and hotel key at the party. Although his chauffeur was there, Kennedy personally drove Kopechne in his black, four-door Oldsmobile 88.

To return from the party site to the Edgartown ferry, Kennedy should have turned left, but he later said he was disoriented and lost, and turned right, headed for the eastern-facing beach. That beach is separated from the main body of the island by a tidal pond called Poucha Pond. There was a one-lane wooden bridge over Poucha Pond called the Dike Bridge. Kennedy drove his car off the bridge; it overturned and came to rest on its roof with its wheels just under the surface.

Kennedy swam free, but Kopechne was trapped.

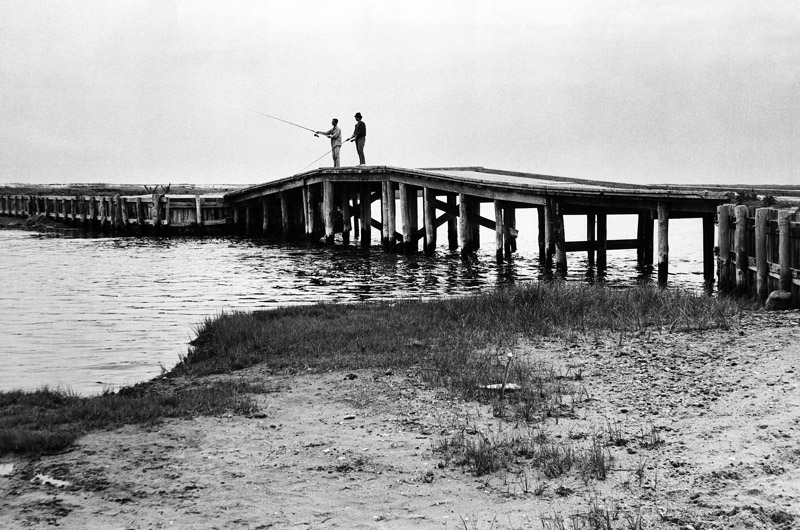

The Dike Bridge

Kennedy left the scene and went back to the Lawrence cottage. He quietly told two of the men there, Joseph Gargan and Paul Markham, about the accident. He later testified that the three of them went back to the Dike Bridge, but neither Markham nor Gargan were able to reach the car.

Kennedy then had them drive him to the ferry landing of the ferry that crosses the narrow channel between Chappaquiddick Island and Martha’s Vineyard. Kennedy claimed he did not wait for the ferry, but swam the 150-yard channel separating Chappaquiddick Island from Martha’s Vineyard and Edgartown. Then he went to his hotel room in Edgartown and went to sleep, never having reported the accident to the police or fire department.

Kennedy did not report the accident to the police for ten (10) hours (and neither did Gargan or Markham). Kopechne died inside the car. By the time Kennedy reported the accident the next day, the car—and Kopechne’s body—had already been found.

John Farrar, captain of the Edgartown Fire Rescue unit, was the diver who recovered Kopechne's body. He testified at the inquest that he found her in the well of the back seat of the car, with her hands clasping the back seat, and her face turned upward to where the air pocket would have been:

“It looked as if she were holding herself up to get a last breath of air. It was a consciously assumed position. . . . She didn't drown. She died of suffocation in [an] air void. It took her at least three or four hours to die. I could have had her out of that car twenty-five minutes after I got the call. But [Kennedy] didn't call.”

Kennedy’s Oldsmobile 88

Kennedy's route from the site of the accident back to the Lawrence cottage took him past four houses from which he could have telephoned for help. The first was "Dike House", 150 yards from the Dike Bridge, occupied by Sylvia Malm, who testified that she was home, had a telephone, and she had left a light on before retiring for the night.

Nothing Kennedy did that night makes sense, unless one assumes he was drunk. And then everything he did makes sense, including going in the wrong direction, driving off the bridge, and not being able to help Kopechne. He didn’t report the accident for ten hours because he needed time to sober up. He swam the channel from Chappaquiddick to Edgartown to help metabolize the alcohol.

Had he worried less about the trouble he was in, and instead had run to the Dike House to report the accident, there is a good chance Kopechne could have been saved.

Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident causing personal injury; he received a two-month suspended sentence (no jail time). It was a scandalously light sentence, but the greater scandal was that the voters of Massachusetts continued to return him to the senate for the next 40 years.

Although he never paid a price in Massachusetts, Ted Kennedy’s presidential aspirations were mortally wounded. He had been expected to run for president in the 1972 cycle, but decided not to, in part because the Chappaquiddick scandal was still recent. He unsuccessfully challenged Jimmy Carter, a sitting president, in the 1980 Democratic Party primaries; Carter easily secured re-nomination, then lost in a landslide to Ronald Reagan. Kennedy died of cancer in 2009, still in the United States Senate.

Helter Skelter - The Manson Murders

On August 8–9, 1969, members of the Manson cult murdered five people in a rented home in west Los Angeles. The victims included actress and beauty queen Sharon Tate and coffee heiress Abigail Folger. The next night, Manson and his followers murdered two more victims, Leno and Rosemary La Bianca, in the Los Feliz district.

Charles Manson was born out of wedlock in 1934 to a 16-year-old girl in Cincinnati, Ohio, and soon began a long, prolific, and varied criminal career. He was sent to Boys Town, a famous facility near Omaha, Nebraska, but after only four days, he and another boy stole a car and a gun, and robbed a grocery store. He was then sent to the Indiana Boys School, a strict reform school, where other students raped him. In 1951, he was transferred to another facility, where he was caught raping a boy at knifepoint. He was then transferred to the Federal Reformatory in Petersburg, Virginia, where he committed a further "eight serious disciplinary offenses, three involving homosexual acts."

Manson was in and out of prison throughout the 1950s and 60s. He was married in 1955, and had a son, but his wife left him during one of his prison stints, and they were divorced in 1958. That same year, Manson was charged with pimping a 16-year-old girl. In 1959, he pleaded guilty to trying to cash a forged U.S. Treasury check; he received a 10-year suspended sentence and probation after his girlfriend told the court that she and Manson were deeply in love and that she would marry Manson if he were given probation. And she did marry him.

In 1960, Manson took his second wife and another woman to New Mexico to pimp them, for which he was charged with violating the Mann Act; that charge was dropped, but the suspension of his ten-year federal sentence for check fraud was revoked, and he was imprisoned. His second wife divorced him during this stint. He was released from federal custody in March, 1967.

Manson then headed for California, and somehow managed to established himself as a guru and cult leader in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district during 1967’s “summer of love.” He started preaching on religious themes, and borrowed his eschatology from the Process Church of the Final Judgment, whose members believed Satan would become reconciled to Christ and the two would come together at the end of the world to judge humanity.

Manson taught his followers that they were the reincarnation of the original Christians, and that the Romans were the “establishment.” He implied that he was Christ; he often told a story envisioning himself on the cross with nails in his feet and hands. He began going by "Charles Willis Manson," saying it very slowly--"Charles' Will Is Man's Son"—implying that his will was the same as that of the Son of Man.

As a cult leader, Manson’s trajectory was not unlike that of Vernon Howell, aka, “David Koresh,” who took over the “Shepherd’s Rod” cult that had split off from the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the 1930s. Both Manson and Koresh implied that they were Messianic figures, both exploited many credulous women, both were interested in music and fancied themselves musicians, and both touched off horrific violence.

By 1969, Manson and about 100 followers, who habitually used hallucinogenic drugs, had set up camp at the Spahn Ranch, an old western movie location in the hills above the San Fernando Valley near Chatsworth. Most of Manson’s followers were young women from middle-class backgrounds who were drawn to the hippie counter-culture of communal living, and were brain-washed and programmed by Manson’s cult.

Manson’s finely-honed ability to lie and manipulate gave him enormous power over others—his “family” obeyed him implicitly—and that power corrupted him utterly, creating a monster. This is the same pattern we see with many other cult leaders, including David Koresh and Jim Jones.

Manson became increasingly irrational. He was convinced that a race war, which he believed was foretold in the Beatles’ song “Helter Skelter,” was immanent, and that he could touch if off by blaming the Black Panthers for hideous murders he and his followers would commit.

In the late spring 1968, Dennis Wilson of The Beach Boys picked up two Manson family girls who were hitchhiking and brought them to his Pacific Palisades house. He returned home the following morning from a night recording session, and met Charles Manson emerging from his house. Wilson and Manson became friends. Wilson paid for Manson’s recording studio time, and introduced him to Terry Melcher, son of Doris Day. Melcher was a record producer and had produced albums for The Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders. Manson wanted Melcher to give him a recording contract, but Melcher was not interested. Manson felt snubbed and wanted to retaliate.

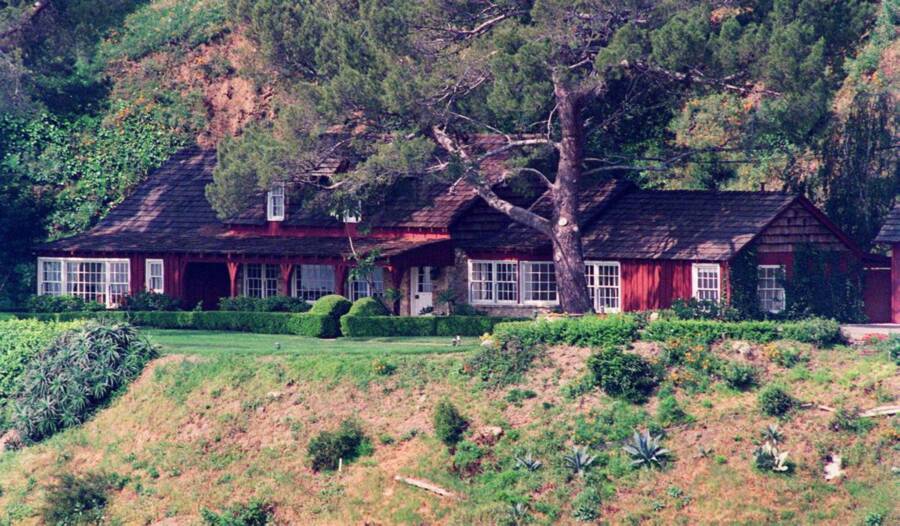

10050 Cielo Drive

Melcher and his then-girlfriend, Candice Bergen, had rented the house at 10050 Cielo Drive, but by early 1969, it was being rented by movie director Roman Polanski and his wife, Sharon Tate. Manson knew that Melcher no longer lived at 10050 Cielo Drive, but decided to start the war there anyway. Manson himself did not go to Cielo Drive. He instructed family members Tex Watson, Susan Atkins, Linda Kasabian, and Patricia Krenwinkel to go to "that house where Melcher used to live, and totally destroy everyone in [it], as gruesome as you can.” He told the women to follow Watson’s instructions.

Roman Polanski was in Europe directing a movie. Those at 10050 Cielo Drive on the night of August 8, 1969, included Sharon Tate, who was eight-and-a half months pregnant, her friend and hairstylist Jay Sebring, Polanski's friend and aspiring screenwriter Wojciech Frykowski, and his girlfriend, Abigail Folger, daughter of Peter Folger and heiress to the Folger coffee fortune. None of them knew anyone in the Manson family.

Two others narrowly avoided being caught up in the massacre. Musician Quincy Jones, a friend of Sebring, had planned to attend that evening but did not, and Sebring had also invited Steve McQueen. McQueen and his girlfriend opted for a quiet night at home.

When the killers arrived, Watson climbed a telephone pole near the entrance gate and cut the phone line to the house. A few minutes later, an 18-year-old student, Steven Parent, drove up to visit the caretaker who lived in the guest house; he was in the wrong place at the wrong time: Watson shot him four times, killing him.

Sharon Tate

Telling Kasabian to keep watch below the gate, Watson cut the screen off a window and entered the house. He then let Atkins and Krenwinkel in through the front door. Frykowski was sleeping on the living room couch; Watson kicked him in the head. When Frykowski asked who he was and what he was doing there, Watson replied: "I'm the devil, and I'm here to do the devil's business.”

Atkins found the house's three other occupants and, with Krenwinkel's help, forced them to the living room. Watson tied Tate and Sebring together by their necks; when Sebring protested the rough treatment of the pregnant Tate, Watson shot him, then stabbed him seven times.

Frykowski, whose hands had been bound with a towel, freed himself and began struggling with Atkins; he fought his way out the front door and onto the porch, where Watson caught up to him, struck with a gun multiple times, stabbed him repeatedly, and shot him twice.

Abigail Folger escaped from Krenwinkel and fled out a bedroom door to the pool area, where Krenwinkel stabbed her and tackled her to the ground. Watson then stabbed Folger 28 times. Frykowski was still alive and was crawling across the lawn; Watson finished him with a final flurry of stabbings.

Abigail Folger

In the house, Sharon Tate pleaded to be allowed to live long enough to give birth, and offered herself as a hostage in an attempt to save her baby. Atkins, Watson, or both killed Tate by stabbing her 16 times.

Manson had told the women to "leave a sign ... something witchy.” Using the towel that had bound Frykowski's hands, Atkins wrote "pig" on the front door in Tate's blood.

The next night, August 10, 1969, Manson himself went with the killers to the home of Leno and Rosemary La Bianca on Waverly Drive in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles. The killers were the same, except that Susan Atkins was replaced by Leslie Van Houten. The murders were similarly bloody, with Rosemary La Bianca being stabbed 41 times.

The Manson atrocity was one of the most horrifying crime sprees in American history. It was shocking both because it was gruesome, bloody, and exceedingly cruel, and because it was utterly senseless, random and without any sane rationale. The public was fascinated by the communal lifestyle of the killers and the strange hold that Manson had over his “family” of young women. 10050 Cielo Drive became the most infamous address in Los Angeles, at least until 875 S. Bundy Drive emerged in the mid-1990s.

Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi’s account of the crimes and the subsequent trial, “Helter Skelter,” became the bestselling true crime book in American history, selling 7 million copies and allowing Bugliosi to live out his life in leisure, a much happier fate than awaited Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden.

Charles Manson was convicted of the Tate-La Bianca murders and sentenced to death, but was spared when a 1972 court decision invalidated all death penalties in California; he was denied parole 12 times and died in prison in November, 2017, from complications of colon cancer. Tex Watson was also sentenced to death, but also had his sentence reduced to life; he is still in prison having been denied parole 17 times. Behind bars, Watson has married, divorced, fathered four children and become an ordained minister. Susan Atkins died in prison in 2009; Patricia Krenwinkle and Leslie Van Houten are still alive and in prison. Linda Kasabian, who was a lookout and never entered the homes, cooperated with Bugliosi as a state’s witness, and testified against the others for 18 days at the trial, thereby escaping jail.

Roman Polanski, now 86, lives in Europe, a fugitive from California justice for the 1977 rape of a 13-year-old girl; his films have won 8 Oscars—six of them subsequent to the statutory rape.

Woodstock - Mud and Music in New York

If the Manson cult represented the evil, depraved underbelly of the late 1960s’ hippie counter-culture, the music festival that became known as “Woodstock” (despite being staged a long way [43 miles] from Woodstock), was an innocent—or at least a far less sinister—manifestation of that same counter-culture. Woodstock was perhaps the apex of the counter-culture movement of the late 1960s and early 70s.

Billed as "an Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music," Woodstock was held at Max Yasgur's 600-acre dairy farm in Bethel, New York, on August 15th through the 18th, 1969. More than 400,000 people attended, far more than the promoters had planned on. Thirty-two acts performed outdoors despite sporadic rainfall.

Four promoters dreamed up Woodstock: Michael Lang, Artie Kornfeld, Joel Rosenman, and John P. Roberts. Roberts and Rosenman financed the project. In April 1969, Creedence Clearwater Revival agreed to perform for $10,000 (equivalent to $68,000 in 2018 dollars). "Once Creedence signed, everyone else jumped in line and all the other big acts came on."

Other performers included Richie Havens, Sweetwater, Arlo Guthrie, Joan Baez, Country Joe McDonald, Canned Heat, Sha Na Na, Santana, the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone, the Who, Jefferson Airplane, Joe Cocker, the Band, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and Jimi Hendrix.

Tickets cost $18 in advance and $24 at the gate (equivalent to about $120 and $160 today). Tickets were sold in advance at record stores around New York City, or by mail. Around 186,000 advance tickets were sold, and the organizers anticipated approximately 200,000 would attend.

Obviously, Woodstock was to be a profit-making venture, but the massive crowds that showed up simply walked through gaps in the fences, and the organizers decided to declare it a free event. The festival itself, and the approximately 80 lawsuits brought by nearby property-owners, nearly bankrupted the promoters, but they owned the film and recording rights, and recouped the money from the hit documentary film that was released in March, 1970.

Swami Satchidananda gives the “invocation.”

The rock subculture of that time was being influenced by eastern religion and the opening ceremony was conducted by Swami Satchidananda, a Hindu mystic and guru.

The site was not equipped to provide sanitation or first aid for the number of people attending; hundreds of thousands found themselves in a struggle against rain, mud, food shortages, and poor sanitation.

Creedence Clearwater Revival didn’t take the stage until 3:30 a.m.; John Fogerty recalled:

“ . . . there were a half million people asleep. These people were out. It was sort of like a painting of a Dante scene, just bodies from hell, all intertwined and asleep, covered with mud. And this is the moment I will never forget as long as I live: A quarter mile away in the darkness, on the other edge of this bowl, there was some guy flicking his Bic, and in the night I hear, 'Don't worry about it, John. We're with you.' I played the rest of the show for that guy.”

Jimi Hendrix was the last act, and performed a two-hour set that included a psychedelic guitar rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner" that segued into "Purple Haze,” a combination that would become part of the sixties Zeitgeist.

Dawn at Woodstock, on August 17, 1969.

Given the enormous throng of almost half a million, the event was remarkably safe; there were only two fatalities: one from drugs and another when a tractor ran over someone sleeping in a hayfield. There were two live births and four miscarriages. In tune with the idealism of the ‘60s, there was a sense of social harmony.

Over the succeeding decades, Woodstock’s reputation has inflated; it is now seen as an epochal event. A pundit recently wrote that if there were a question on the census asking whether you attended Woodstock, over 5 million would claim to have been there.

It was a product of its time, when the counterculture was at its peak and rock music was less commercialized. Various attempts to recapture that moment have failed. Although there was a modest series of concerts there in 2009 celebrating the 40th anniversary, a 50th anniversary concert planned for this year was cancelled.

My editorial comment: In 1969, rock music was an adolescent form celebrating sex, drugs, and—because most parents did not approve—rebellion. Over the past half-century, however, a strange thing happened: the counterculture became the mainstream culture. The music of sex, drugs and rebellion has become the dominant form of popular music. It is all-pervasive, and few grown-ups disapprove anymore. In fact, there don’t seem to be many grown-ups left in America. My age group, the 50-somethings, are all on Facebook posting how cool it was to see their favorite ‘80s rock band in concert. The culture of rock music has created a nation suspended in permanent adolescence.

The church is not immune to this cultural sickness. Many of us have experienced tuning in to a rock music station and, several minutes later, noticing that there were nominally “Christian” lyrics being “sung” to the music. Putting Christian lyrics to rock music is like Constantine marching his legions through the river and declaring them baptized. It’s like calling a local pagan goddess the Virgin Mary of Guadalupe. It’s rubbish.

Hurricane Camille - A Two-Part Disaster

Hurricane Camille was the second most intense hurricane ever to strike the United States. It originated as a tropical depression on August 14, 1969, and strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane before striking the western part of Cuba on August 15. It traveled northwesterly, into the Gulf of Mexico, where it rapidly intensified into a Category 5 hurricane, the most dangerous category.

Camille made landfall at 11:30 p.m. on August 17, 1969, in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. At peak intensity, the hurricane had a minimum pressure of 900 mbar. This was the second-lowest pressure recorded for a U.S. landfall. Only the 1935 Labor Day hurricane had a lower pressure at landfall.

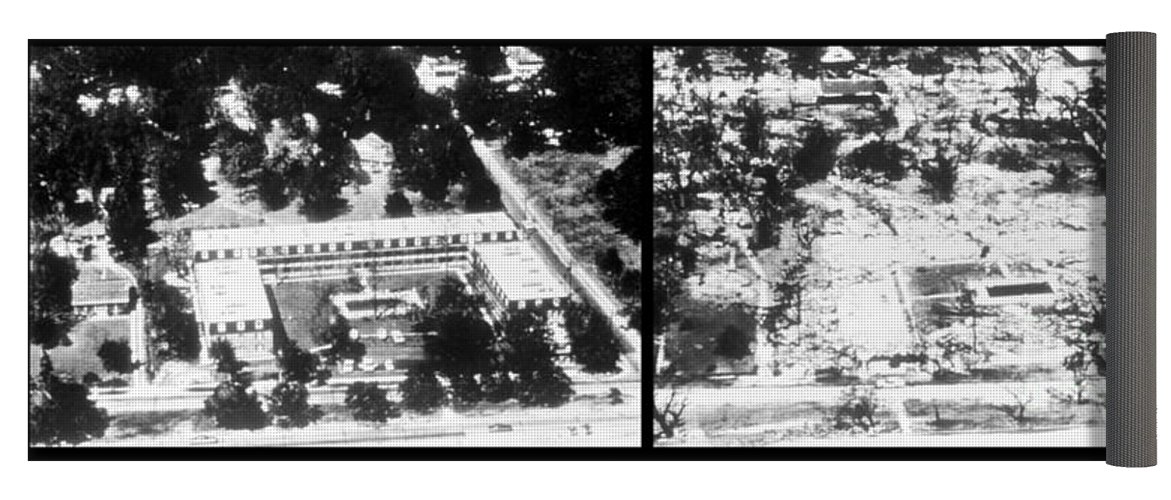

The Richelieu apartment complex - wiped away by Camille

Camille caused tremendous damage from both high winds and an enormous storm surge of 24 feet (7.3 m). Many structures along the gulf coast of Mississippi were destroyed. The storm killed 143 people along Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana coast, most of whom lived right on the coast and had neglected to evacuate.

As Camille pushed inland, it became a tropical depression, turned north, then turned east and traveled over the Appalachian Mountains, where it dumped tremendous rainfall in a short amount of time.

Most of the rainfall occurred in Virginia during a 3 to 5-hour period on the night of August 19–20. Many rivers flooded across the state, with the worst being the James River in Richmond with a peak crest of 28.6 feet (8.7 m). In the mountain slopes between Charlottesville and Lynchburg, more than 26 inches of rain fell in 12 hours, but the worst was in Nelson County where 27 inches (690 mm) fell.

Aftermath of Flooding on Davis Creek, Nelson County, VA.

The loss of life from excessive rainfall over Appalachia was greater than on the gulf coast: 153 people perished in Nelson County, Virginia, and nearby locales, mostly killed by landslides from saturated, slumping hillsides.

Camille then headed out to sea again over the coast of Virginia.

Camille did some $1.42 billion in damage (in 1969 dollars—equivalent to $9.7 billion in 2018 money). In all, 8,931 people were injured, 5,662 homes were destroyed, and 13,915 homes experienced major damage.

“Already the restraining Spirit of God is being withdrawn from the world. Hurricanes, storms, tempests, fire and flood, disasters by sea and land, follow each other in quick succession. Science seeks to explain all these. The signs thickening around us, telling of the near approach of the Son of God, are attributed to any other than the true cause.”

“Calamities, earthquakes, floods, disasters by land and by sea, will increase. God is looking upon the world today as he looked upon it in Noah’s time. He is sending his message to people today as he sent it in the days of Noah. There is in this age of the world a repetition of the wickedness of the world before the flood.”

Perhaps Hurricane Camille was God’s show of displeasure with the events of the summer of 1969.